The Jewish Tavern as Part of the Polish Landscape: Interview with Glenn Dynner

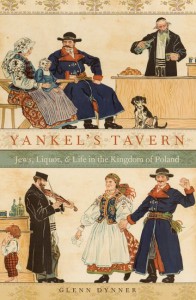

In Yankel's Tavern: Jews, Liquor & Life in the Kingdom of Poland (Oxford University Press, 2014), Glenn Dynner examines the iconic Polish Jewish tavernkeeper in the Kingdom of Poland.

In Yankel's Tavern: Jews, Liquor & Life in the Kingdom of Poland (Oxford University Press, 2014), Glenn Dynner examines the iconic Polish Jewish tavernkeeper in the Kingdom of Poland.

In nineteenth-century Eastern Europe, the Jewish-run tavern was often the center of leisure, hospitality, business, and even religious festivities. This unusual situation came about because the nobles who owned taverns throughout the formerly Polish lands believed that only Jews were sober enough to run taverns profitably, a belief so ingrained as to endure even the rise of Hasidism's robust drinking culture.

As liquor became the region's boom industry, Jewish tavernkeepers became integral to both local economies and local social life, presiding over Christian celebrations and dispensing advice, medical remedies and loans. Nevertheless, reformers and government officials, blaming Jewish tavernkeepers for epidemic peasant drunkenness, sought to drive Jews out of the liquor trade. Their efforts were particularly intense and sustained in the Kingdom of Poland, a semi-autonomous province of the Russian empire that was often treated as a laboratory for social and political change.

Historians have assumed that this spelled the end of the Polish Jewish liquor trade. However, newly discovered archival sources demonstrate that many nobles helped their Jewish tavernkeepers evade fees, bans and expulsions by installing Christians as fronts for their taverns. The result—a vast underground Jewish liquor trade—reflects an impressive level of local Polish-Jewish co-existence that contrasts with the more familiar story of antisemitism and violence.

Buy the book.

Glenn Dynner is Professor of Judaic Studies at Sarah Lawrence College and the 2013-14 Senior NEH Scholar at the Center for Jewish History. In addition to Yankel’s Tavern, he is author of "Men of Silk": The Hasidic Conquest of Polish Jewish Society (Oxford University Press), winner of the Koret Publications Prize and finalist for the National Jewish Book Awards. He is editor of Holy Dissent: Jewish and Christian Mystics in Eastern Europe (Wayne State University Press); and co-editor of a forthcoming volume of Polin and of Warsaw, the Jewish Metropolis: Essays in Honor of the 70th Birthday of Professor Antony Polonsky.

He is interviewed here by Yedies editor, Roberta Newman.

RN: How, when, and why did tavernkeeping become such a Jewish specialty in Poland and Lithuania? How did the Jews become tavernkeepers?

GD: We have to remember that the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth was a very agrarian society, dominated by the nobility. They were even, arguably, more powerful than the kings, because the kings were elected, and foreign. So these nobles would lease the enterprises on their estates, rather than running them themselves. Those whom they chose to lease these enterprises were usually Jews. Jews had literacy, Jews had the mobility, and they were politically non-threatening. There were a host of reasons. As the grain trade begins to decline, and because of tariffs and other developments, you couldn’t sell grain very cheaply to Western Europe. The nobility increasingly began to turn that grain into vodka, and sold it to its peasants by means of taverns and distilleries. These were, in most cases, leased to Jews.

So the fact that the Jews are sort of a trusted middleman element—I even call them a captive service sector—means that they are the natural candidates to run these taverns and distilleries, once the liquor trade begins to account for a greater and greater proportion of the estate economy. Added to that is the myth of Jewish sobriety. The nobility believes that Jews won't drink up a product. There are other reasons, too, such as the idea that they can better extend hospitality to travelling merchants, who are also increasingly Jews.

And so the system basically works. You have this supposedly sober, captive element of the population that seems to do the best job running your taverns and distilleries. When they've experimented with peasants it's been a disaster. When they've experimented with nobility, fellow noblemen, often landless, it's also been a disaster, because you can't push them around. They're more proud. They're more politically ambitious. And so Jews fit that niche just perfectly. And that's how it goes for centuries.

RN: You referred to Jews as "captive." What do you mean by that?

GD: By "captive" I mean that Jews were not allowed to own land, for the most part. The fear was, way back in the Middle Ages when Jews were first being admitted to Polish lands, that they would buy everything out, buy out Poland. And so they can't really become land owners. They can't really attain nobility in most cases. There's a limit to the occupations they can pursue. Only trade, crafts, lease-holding.

Also, where else are Jews going to move to? There are all kinds of restrictions placed on Jewish residence throughout Europe. Eventually America becomes a safety valve. But, for the most part, Jews are kind of stuck in Eastern Europe. But they're not just stuck, they like it there, because they have a way of making a living, of being relatively secure and prosperous. But they can't enter the professions. They can't become ennobled. They can't become farmers in the sense of owning vast tracts of land. They're limited in what they can pursue, and that's why I use the term "captive."

RN: After the partitions of Poland in the late eighteenth century, Jewish tavernkeeping came under increasing attack by reformist forces in the government. Why? What was the critique?

GD: If you just take their word for it, it's that the more the nobility takes this grain and turns it into vodka, and sells it to its peasantry, the more drunkenness becomes a problem. They didn't call it "alcoholism" back then. It hurts productivity, it ruins families economically—it's an epidemic problem. So who are they going to blame? They blame the Jewish tavernkeeper.

But if you dig a little deeper you realize that these taverns were much more than just taverns. They were hotels, restaurants, stores, banks. The Jewish tavernkeeper would often offer medical remedies and mediate conflicts. Jews were in a position of real power—not in the same way as the nobleman, who actually owns the tavern, but still, they have relative power. And it's lucrative, and as liquor trade increases in importance, having the members of an out-group in such a central position rubs people the wrong way. And so a lot of the outcry occurs as these taverns are becoming more lucrative.

That's probably the reason why the reform-minded nobility, in alliance with tsarist officials and their Polish representatives in the kingdom of Poland, begin to legislate, decreeing special fees, restrictions, and finally, bans on Jewish tavernkeeping.

RN: So Jewish tavernkeeping went a little bit underground in the nineteenth century?

GL: Yes. And the fascinating thing is that the Jewish tavernkeeper is so crucial to the local economy and so embedded in the local society that the local nobility and the other local Christians would help conceal and protect the Jewish tavernkeeper. They covered for him. They did so in all kinds of interesting ways: the Christians served as fronts for these taverns, they lied to state officials who came in and investigated. They had all kinds of ways of circumventing what they saw as state intrusion on what by then was a very traditional way of life.

So you can see that the system basically works at the local level. It's kind of an integration. It's not social integration, but it's definitely economic integration. You can't have an underground liquor trade without the complete support and encouragement of the local nobility and local Christians. Everybody is covering: it's kind of an open secret. But they do their part in ensuring that this Jewish liquor trade is able to continue. That's what I found so fascinating and surprising.

Most historians who just had read the legislation and took it at face value seemed to be oblivious to the fact that Poland's economy, essentially, which was so dominated by the liquor trade, was virtually underground. At least its service sector was.

RN: There do seem to be a lot of myths associated with Jewish tavernkeeping. First of all, the nobles' myth that only the Jews are capable of running their liquor concessions (though maybe that wasn’t a myth), and then the reformers’ charges that Jewish taverns were responsible for so many societal ills. And then, in your book, you set out to debunk another myth that Jewish tavernkeeping was largely a thing of the past as early as the mid-nineteenth century. So how and why did that last misconception develop?

GD: It's propagated first by state officials who want to convince themselves that the "problem" has been solved. They're willing to turn a blind eye in order to sustain that assertion. The problem is, when the first generation of historians begins looking at this in the early twentieth century, they buy into it, too. They believe the officials and the idea that tavernkeeping had died out supports their own, largely Marxist inclinations. Tavernkeeping is seen as part of the old, feudal system, as an emblem of backwardness. The historians want to show that Jews in Eastern Europe urbanized rapidly, industrialized, and were quintessentially modern—and tavernkeeping didn't fit the story.

From our post-1989 perspective, we don't have as much invested emotionally in this. We can say with a great deal of certainty that Jewish tavernkeeping lasted throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, even after it was outlawed again, in the twentieth century, in the 1930s. I think I may be the first to be resisting that myth because I have less invested in it.

RN: Was there also some kind of stigma attached to tavernkeeping? What was the rabbinic attitude, the maskilic attitude toward it?

GD: In fact, virtually everybody—reformists, the state, the Christian clergy, the maskilim, and even the rabbis—were opposed to Jewish tavernkeeping. The only group that was in favor of Jewish tavernkeeping, besides the tavernkeepers themselves, were the very Christians they were supposedly "exploiting," the locals, because they relied so heavily on the Jewish tavernkeeper. Every other group wanted them out.

The stigma came from the idea that it's a sleazy business. It's a dirty business. You're selling an intoxicating, addictive substance to easily manipulated peasants. They're running up their tabs, they're going into debt. The temptation to cheat is very powerful. There isn't a great deal of sympathy for the drunken peasant. So all groups look at this as a problem.

The rabbis have a different reason. The rabbis stigmatize the Jewish liquor trade because the tavernkeepers had to keep their taverns running on the sabbath and on Jewish holidays, not only to be profitable, but also: if a nobleman wants to drink, you're going to tell him, "I'm sorry, it's Saturday"? It's just not going to work. So the rabbis feel compelled to elaborate legal fictions where they say things like, "If you sell the tavern to a gentile partner, and they own 1/7th of the profit [the equivalent of the sabbath day in a seven-day week], you can find a way around these prohibitions." But they didn't like it and were very uneasy with these legal fictions. And some rabbis would rail against Jewish tavernkeeping. In rabbinic polemics you even see Jewish tavernkeepers being blamed for the 1648 Khmelnytsky massacres.

RN: Who is the "Yankel" of Yankel's Tavern?

GD: Yankel is an iconic literary figure in Adam Mickiewicz's epic poem "Pan Tadeusz," which every Polish school child knows, and reads, and doesn't always enjoy. But Mickiewicz was the first Polish author to present a positive Jewish tavernkeeper. He saw the tavernkeeper—the Jewish tavernkeeper—as a unifier, because when the characters of the poem enter the tavern after church, there are members of all walks of Polish society gathered under the same roof, and Yankel is serving them, and there's a spirit of togetherness. There is a sense that Jews might actually serve as a unifying factor in a fractious, post-partition Polish society, where you have the loyalists who are supporting the Russian colonial power and there are Polish insurrectionists who want to fight it. There is the clergy. Everybody is at odds with everyone else and there's a hope that the Jewish tavernkeeper can unify them.

And he presents the Jewish tavern as a fixture of the Polish landscape. It's not something foreign, it's not something necessarily negative. It's part of the landscape. That sentiment unfortunately was not sustained in Polish Romantic literature, and, in essence, the Jewish tavernkeeper becomes a very negative, polarizing figure who's depicted as being responsible for exploting the peasantry, and who's a traitor who gives information to the Polish rebels, or to the tsarist army. In some works of fiction you have scenes where the Jewish tavernkeeper is hung from a pine tree.

RN: So this is a recurring theme?

GN: It’s a recurring theme of both the 1830-1831 and 1863 insurrections. What I found is that there actually were Jewish tavernkeepers who spied for the Russians. There were Jewish tavernkeepers who spied for the Polish rebels. But the majority seemed to just want to remain neutral and to survive the ordeal with life and livelihood intact.

RN: What led you to this topic?

GD: When read about tavernkeeping before, I thought of it as something that had been a thing of the past. Historians only spoke of its demise. When I went to the archives searching for a topic for my second book, I began flipping through archival files that had been analyzed by Raphael Mahler, by Arthur Eisenbach, by Ignacy Sziper, and other pioneers of East European Jewish historiography. And the words "Jews," "taverns," and "drunkenness," just kept popping out. Sometimes on every page. And I started to see I wasn't just dealing with a phenomenon—I was dealing with an obsession on the part of state officials and the idea that all of Poland's problems could be solved by dealing with this problem of the Jewish tavernkeeper.

At the same time, I started seeing case studies from long after taverns were supposed to be a thing of the past. The case studies are investigations which show that not only is there a Jewish tavernkeeper still selling liquor to everybody, but that all the locals are covering for him. And that was interesting because it undercuts the image of antisemitism, violence, and persecution that we inherit as a post-Holocaust generation. This is a very different story, a story of coexistence. And that's where it became really interesting and fascinating.

RN: What other archival sources did you look at?

GD: When I discovered the Eliyahu Guttmacher collection at YIVO, it was like finding a hundred dollar bill on the sidewalk. This is a collection of thousands and thousands of kvitlekh, or petitions, to a non-Hasidic miracle worker from the early 1870s, written in Hebrew and Yiddish. They’re mainly from the kingdom of Poland. People would come over the border with their petitions, and each petition really told a story. And many of them would state their occupation, and many were tavernkeepers.

So this became a vital source about what it was like to be a Jewish tavernkeeper, what the problems were. Sometimes their problems weren't related to tavernkeeping, and they seemed to be doing quite well, very prosperous. But often their taverns were facing pressures. The newly emancipated peasantry seemed to be beginning to open up their own taverns. And, of course, this was more proof positive that Jewish tavernkeeping still existed.

And one thing I really gained from reading the Guttmacher kvitlekh was a deep sense of anxiety. It was a tough occupation. There were worries coming from all angles, not just about your clientele, who could be raucous and violent. Not just about soldiers who would come and threaten your enterprise, but the state itself. It may have been looking the other way, but tavernkeeping was technically illegal, and the spotlight could fall on you at any time. You had informers. Sometimes the peasants who were competing against you would inform on you. Sometimes fellow Jews would inform on you. Sometimes your own competitors who were also tavernkeepers. In other words, it was a very tense existence. And we don't get that from reading literature, although I found literature to be a really valuable source, too. When Mendele Mokher Sforim presents his tavernkeepers, they're usually quite light-hearted and you don't get that deep sense of fear.

Jewish tavernkeepers were part of local life. Every wedding, every funeral would begin in the church, but it would then walk in procession to the tavern. Jews, in order to observe their own holidays, would rely on the local Christians to run their taverns on those days, and accept money on those days. So even in terms of each other observing their own religious festivities, they were dependent on each other. And that's what the tavern can show us, is that sense of mutual dependence that has been lost. It's really important to study the Holocaust, and to learn about pogroms, but not to let it obscure this rich and vital Jewish existence in Eastern Europe that was also there. And that’s what I wanted to get across in my book.

The last piece of this is that when I gave my first talk here at YIVO, at the Ruth Gay Seminar, I was very surprised when almost a hundred people showed up because I had no idea if anyone knew about this phenomenon. They came out of the woodwork and they came at me waving documents showing that their grandparents had run taverns in the old country. This only further affirmed my suspicion that this was a flourishing phenomenon: a traditional, but flourishing occupation that lasted deep into the twentieth century. It hadn't died at all, and, in fact, it was a rubric, a window into the entire society.

Transcribed by Alix Brandwein. Interview edited for length and clarity.