The Frankfurt School, Jewish Lives, and Antisemitism: Interview with Jack Jacobs

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

On Wednesday, April 29, 2015, at 6:30pm, in a program co-sponsored by YIVO and the Leo Baeck Institute, CUNY Professor Jack Jacobs will present original research about the Frankfurt School, including little-known materials from the YIVO Archives, in a discussion about the views of members of the Frankfurt School on the State of Israel. Jacobs' book, The Frankfurt School, Jewish Lives, and Antisemitism, was recently published by Cambridge University Press. The event will be chaired by NYU Professor Marion Kaplan.

On Wednesday, April 29, 2015, at 6:30pm, in a program co-sponsored by YIVO and the Leo Baeck Institute, CUNY Professor Jack Jacobs will present original research about the Frankfurt School, including little-known materials from the YIVO Archives, in a discussion about the views of members of the Frankfurt School on the State of Israel. Jacobs' book, The Frankfurt School, Jewish Lives, and Antisemitism, was recently published by Cambridge University Press. The event will be chaired by NYU Professor Marion Kaplan.

Buy tickets to the event.

Buy the book.

The Frankfurt School was a group of scholars in the Institute of Social Research, which was founded in Frankfurt am Main in 1923 as a Marxist-oriented, academic institution focused on the study of economics, labor history, and socialist history. But this orientation shifted in 1930 with the advent of a new director, Max Horkheimer, who departed from standard social scientific methodology by exploring a more interdisciplinary analysis of the big social, economic, and political issues of the day, bringing in insights not only from the social sciences, but also from fields in the humanities, such as literary criticism.

In this interview with Yedies, Jacobs gives an example of this new approach. “One of the earliest projects utilizing this methodology was Erich Fromm’s inquiry into the mystery of why the German proletariat wasn’t behaving the way that Marxists had anticipated. Why were the fascist parties growing in power and why weren’t the workers resisting this rise in greater numbers? This was, in a sense, the question of the 20th century: how to explain the rise of Nazism." Fromm used Freudian insights to come up with a theory about what he called “the character structure” of German workers, positing that they were unlikely to challenge the social and political power structure because of the hierarchical nature of German society, which extended even into the home, influencing children’s relationships with their fathers, the authority figures in the family. “German workers were inclined to accept and to support strong leaders who would tell them what to do.”

What came to be known as the Frankfurt School was a small circle of scholars around Horkheimer who employed this interdisciplinary approach, which they called Critical Theory, in their work. “It was new,” Jacobs notes. “It doesn’t mean that it was altogether unique or that no one else had tried it, but the members of the Frankfurt School all had similar politics—leftist politics—and they had comparable types of upbringings, and, as a result, despite the fact that we’re talking about people creating in a very disparate range of disciplines, they were able to cooperate with each other and come to important insights. In addition to people with training in sociology, people with training in psychoanalysis, they also had people with great insight into literary criticism, and other disciplines, such as music. And they were able to bring this approach to bear to provide real insight in unexpected ways and directions.”

Over time, these scholars, who, in addition to Horkheimer and Fromm , included Herbert Marcuse, Theodore W. Adorno, and Leo Lowenthal, became some of the most prominent intellectuals of the 20th century. They were at the height of their influence in the 1960s and 1970s, but remain highly influential to this day.

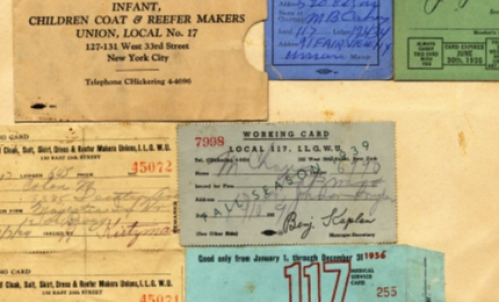

The inspiration for Jacobs’ book came in the 1990s when he was doing research in the Tamiment Library at New York University on aid provided by the Jewish Labor Committee to German Jewish refugees. Among the hundreds of boxes he looked through, he came across a 1,500-page typescript, a study on antisemitism among American workers. Written in the 1940s by exiled members of the Institute of Social Research, under the supervision of Adorno, it had never been published. "It was a bombshell that was too hot to handle," Jacobs explains. The findings of the study were that antisemitism was far more prevalent among American workers than expected. This was not a message that gibed with wartime American propaganda, which sought to paint a picture of the U.S. as a tolerant society in sharp contrast to Nazi Germany. Some of the scholars were in the U.S. on emergency visas and the Institute of Social Research was tenuously based at Columbia University. "The scholars decided that they had to tread lightly and so they didn't rush to publish the study." By the time the war ended, members of the group had moved on to other things, particularly Adorno, who was already at work, with other scholars, on the seminal sociology book, The Authoritarian Personality. “The moment had passed and the study was never published.”

Finding the study led Jacobs to become more curious about the lives and motivations of the Frankfurt School scholars, all of whom were (in whole or in part) of Jewish origin. "My book focuses more on how their Jewish backgrounds brought them to the Institute of Social Research than on how their Jewishness had an impact on their work,” he explains. “The scholars were active in Frankfurt on a full time basis in the period following Horkheimer’s accession to the directorship and before they fled the Nazis. They came to the Institute of Social Research on Jewish paths—different from one another—but all of which differentiated their lives and careers from those of their non-Jewish peers."

Jews were very prominent on the left in Central Europe. “There were many reasons for this,” Jacobs notes, “but it had a great deal to do with the marginal positions that Jews played in European societies. They were locked out of many spheres of life. In many places, they didn't have access to careers in the military or the government." This led some Jews to seek alternative approaches to participation in civic life, such as activity in left-wing political parties or institutions with a left-wing orientation, such as the Institute of Social Research. "It's not that the Institute of Social Research sought to purposely hire only Jews. But it attracted people who had similar backgrounds, who were sympatico. These people were looking for a group who would understand and accept them."

For example, one latecomer to the Institute of Social Research, Herbert Marcuse, first began working there in 1933. "He was extremely educated and intelligent, a student of Heidegger, but he was blocked from advancing in his academic career despite the profundity of his early work,” Jacobs reports. “Whether it was because of Heidegger's antisemitism or the mood of the day, he was not allowed to advance." Influential friends arranged a job for him at the Institute of Social Research, in Switzerland, where he worked in the Geneva office.

Though Jacobs shies away from drawing explicit connections between the Jewish backgrounds of the members of the Frankfurt School and their thoughts and work in pre-Nazi era Frankfurt, he notes that later in his career, Horkheimer came to believe that Jewish ideas did indeed form the backbone of Critical Theory itself. "He told interviewers any number of times that Critical Theory had, as a core contention, that it was not their task to paint in great detail what future society will look like. Their task was to point out what had happened and what was happening at the moment. And he thought that this orientation came from Judaism, from the central tenet that one does not worship idols, that one does not explicitly name God." Jacobs adds, "I think where he was coming from is that you can take techniques and methodologies and use them for subjects other than the subjects for which they had originally been created. So too did they think that there were certain Jewish concepts that rang true, even if they weren’t using them in the ways that religious Jews understood them." But this was an insight that came to him late in life. "In the 1920s and 1930s, he would have been the first to deny that Judaism had any impact on his thought or his take on society."

Jack Jacobs

Jack JacobsJack Jacobs is a professor of political science at John Jay College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. In addition to The Frankfurt School, Jewish Lives, and Antisemitism, he is the author of On Socialists and “the Jewish Question” after Marx (1992), and Bundist Counterculture in Interwar Poland (2009). He was the editor of Jewish Politics in Eastern Europe: The Bund at 100 (2001), and is currently editing Jews and the Political Left, which is under contract with Cambridge University Press.

Marion Kaplan is the Skirball Professor of Modern Jewish History at NYU. She is a three-time National Jewish Book Award winner for The Making of the Jewish Middle Class: Women, Family and Identity in Imperial Germany (Oxford University Press), Between Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany (Oxford University Press), and Gender and Jewish History (with Deborah Dash Moore; Indiana University Press), as well as a finalist for Dominican Haven: The Jewish Refugee Settlement in Sosua (Museum of Jewish Heritage). Her book on the Nazi era also won the Fraenkel Prize in Contemporary History from the Wiener Library, and The Making of the Jewish Middle Class won the American Historical Association Conference Group in Central European History Book Prize.