Survivors and Exiles: Interview with Jan Schwarz

In his new book, Survivors and Exiles: Yiddish Culture after the Holocaust (Wayne State University Press), Jan Schwarz challenges assumptions that Yiddish literature died out after the Holocaust by painting a portrait of a culture that remained alive and in dynamic flux, especially in the two-and-a-half decades after the end of World War II. Yiddish writers and cultural organizations fostered publications and performances, collected archival and historical materials, and launched new, young literary talents. His book charts a transnational post-Holocaust network in which the conflicting trends of fragmentation and globalization provided a context for Yiddish literature and artworks of great originality.

In his new book, Survivors and Exiles: Yiddish Culture after the Holocaust (Wayne State University Press), Jan Schwarz challenges assumptions that Yiddish literature died out after the Holocaust by painting a portrait of a culture that remained alive and in dynamic flux, especially in the two-and-a-half decades after the end of World War II. Yiddish writers and cultural organizations fostered publications and performances, collected archival and historical materials, and launched new, young literary talents. His book charts a transnational post-Holocaust network in which the conflicting trends of fragmentation and globalization provided a context for Yiddish literature and artworks of great originality.

Jan Schwarz is associate professor of Yiddish studies at Lund University, Sweden. He began this position in 2011 after having taught Yiddish language and literature at University of Pennsylvania, University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, Northwestern University, and University of Chicago. He is the author of Imagining Lives: Autobiographical Fiction of Yiddish Writers, as well as numerous critical articles about Jewish life-writing, Holocaust Literature, modern Yiddish culture, and Jewish American literature; and he is the translator of Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the Dairyman into Danish.

Buy Survivors and Exiles: Yiddish Culture after the Holocaust.

Schwarz is interviewed here by Yedies editor Roberta Newman.

RN: What drew you to this subject in the first place? Why did you decide to write this book?

JS: My first book, Imagining Lives: Autobiographical Fiction of Yiddish Writers, was about what I call “life writing,” and was an analysis of a particular literary genre in Yiddish literature. Working on that project led me into studying Yiddish and the Holocaust. This was a new thing for me because I’ve never really been particularly interested in studying the Holocaust, but I became naturally drawn to the topic and wanted to really understand it, particularly its Yiddish dimension. And I soon came to realize that there is very little in the way of a comprehensive examination of what I call “post-Holocaust Yiddish Culture,” though there are, of course, many independent studies of various aspects of Yiddish culture after the Holocaust. That’s how it started: I thought that there was a gap in the scholarly literature and I was drawn to the topic.

RN: Did Yiddish writers after the war try to rebuild the world of Yiddish literature?

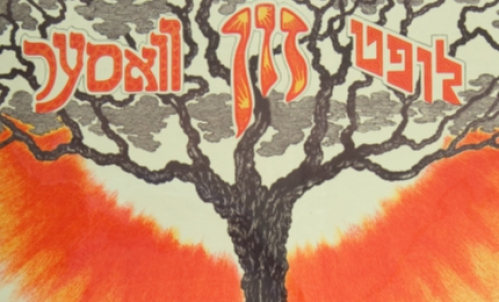

JS: My book is an attempt to map out what I call the “transnational Yiddish culture” that in many ways continued after the Holocaust. There is this idea out there that Yiddish culture stopped, was more or less eliminated, or at least that it severely declined after the Holocaust. But my thesis is the exact opposite, that it not only continued and developed, but it actually, to a certain extent, was revived after the Holocaust, and in fact, played a very crucial role as a response to the Holocaust. It was a culture that put Holocaust commemoration at front and center and tried to keep alive the memory of a civilization in Europe that did not exist anymore.

Also, it continued as a transnational phenomenon. Even if the main centers of Yiddish culture in Europe did not exist anymore, there were still survivors— survivors and exiles—in various locations, such as Montreal, New York, Buenos Aires, Tel Aviv, and even in Warsaw, who continued to work and to publish books. And there were even new young writers. That’s also something that most people don’t realize. We tend to think about the post-war Yiddish writers as an aging group, but there was actually a new young generation of writers that came forward in the 1940s and 1950s, such as Chava Rosenfarb, Leib Rochman, and of course Eliezer [Elie] Wiesel, and others.

So my book is very much about mapping what happened to Yiddish culture after the Holocaust in various centers all over the world and the interaction between the centers.

RN: You’re known as a literary scholar but for this book you had to balance literary scholarship with being a historian.

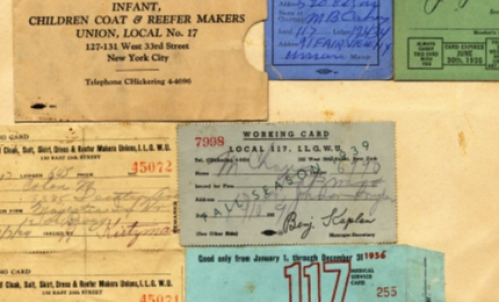

JS: I’ve been trained as a literary scholar to look at literature and analyze literature, and here I had to work also as a cultural historian. I did quite a bit of archival research for this book, to an extent that I didn’t do for my first book. Survivors and Exiles is based very much on primary sources, like, for example, materials from archives of the 92nd Street Y and YIVO. There were also recordings from different cultural events that took place at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal. That was very rich material which opened up a whole world of Yiddish cultural performance that you can’t really find anywhere else. You can’t actually get a full sense of the performative aspect of Yiddish culture from texts alone.

RN: What other primary sources did you consult in the writing of the book?

JS: The letters of Yiddish writers were very important, and another key source was Dos poylishe yidntum (Polish Jewry), a book series: 175 books published in Buenos Aires in 1946-1966. It’s not that it has been entirely forgotten but there is very little secondary literature about it and it was a very important endeavor. Dos poylishe yidntum became a cornerstone, as well as a kind of paradigmatic example of this culture: it was a collective project about Polish Jewry, its history, its culture, and also, very importantly, about its destruction.

RN: You focus on both well-known writers like Isaac Bashevis Singer and lesser-known writers. Can you comment on that? Who are the major figures you’re writing about?

JS: I do indeed focus on seven major figures. Along with Isaac Bashevis Singer, writers in the well-known category include Avrom Sutzkever and Chaim Grade. Yankev Glatshteyn is also pretty well-known, as was Aaron Zeitlin. And then, a couple of writers who are less well-known, but who were very central in the revival and continuation of Yiddish culture after the Holocaust were Chava Rosenfarb in Montreal and Leib Rochman in Jerusalem. So those are the seven writers that I focused on in this book.

RN: So what motivated these writers to continue writing in Yiddish? For instance, Sutzkever moved to Israel, and so he could have learned Hebrew and tried to write in Hebrew, right?

JS: Well, you are already kind of answering your own question. The thing is that it’s very hard to switch languages when you start as a writer if you are not a teenager, and he was definitely not a teenager when he came to Israel; he was in his early thirties. And most of these writers, they were in their thirties, and some of them were older, and they couldn’t just switch languages.

But that’s not really the point here, because actually and surprisingly, some of the writers did switch languages. The best-known example is, of course, Elie Wiesel, who published his first book in Yiddish, Un di velt hot geshvign (And the world was silent). He later wrote a shorter version of the book in French and that started his career as a French writer. So, he was able to switch. And he didn’t write any other books in Yiddish. But, in order for him to be able to do that, he had to publish his first book in Yiddish and get that kind of recognition. He wouldn’t have been able to just start out on his own by writing in French or English.

RN: So, it wasn’t really a choice for them to write in Yiddish— it was a necessity, it was their voice. Did they also feel that they were making a statement by writing in Yiddish?

JS: It was a necessity and it was beyond questioning. It was who they were as Jews and human beings. Many of them had written prolifically during the war under very extreme circumstances. I present some examples of that in the first section of the book. Chava Rosenfarb started out as a Yiddish writer in the Lodz Ghetto—where she belonged to a group of poets with Miriam Ulinover, who was their mentor in the Lodz Ghetto— and she started to write there. That’s where Rosenfarb became very close friends with Simkhe-Bunim Shayevitsh, who was a Yiddish poet. And this was very important for her decision to pursue a career as a Yiddish poet, and later on, as a great Yiddish novelist in Montreal. And another example is Leib Rochman, who kept a war diary while he was in hiding. He was hiding with four other people outside his home town, where the ghetto had been liquidated, and he had managed to escape with his wife and three other people. That’s where he started to write his diary, which was revised after the war and became his first published book in Yiddish.

And the third example is probably the most dramatic example, and in many ways the most paradigmatic of what I’m talking about. Sutzkever wrote all the way through the war, in the ghetto, and in the woods. When he was a leading member of the Paper Brigade, the group that secretly hid cultural treasures from the Nazis in Vilna, he sat in the YIVO building and he wrote his poetry and he never stopped. From the moment the Germans occupied Vilna he continued to write all the way through.

For these Yiddish writers, it was necessity to continue to be productive and creative, and after liberation that continued. For me, it was very life-affirming to learn that most of these writers had incredibly creative lives that continued in old age, in their seventies and eighties. They saw themselves as a generation that came from Europe and that had survived. Some of them had managed to come here prior to the war (Glatshteyn, for example), and Zeitlin escaped at the last minute. But they were all totally committed to Ashkenaz and the memory of Ashkenaz, and to continuing that cultural tradition in Yiddish.

RN: Have you written here about a chapter in Jewish history that’s over, or is it still ongoing?

JS: It’s still ongoing and it’s still in process. The particular culture that once existed and which was, in many ways, a last blossoming of Ashkenaz won’t come back. But it’s still an ongoing culture. Some of the writers are still very influential and have had an impact on American, Hebrew, German, French, and Russian writers. So there is still a process of cross-fertilization and it is not a closed chapter. And by mapping this culture, I also hope that I’m making it accessible to more people, making them aware of these great writers. Many of them have been translated into other languages and this is an attempt to bring them into the mix when you talk about Jewish literature and Jewish culture. These writers should definitely be part of that discussion.

Transcribed by Sydney Hertz. Interview edited for length and clarity.