Janet Hadda (1945 – 2015)

Janet Hadda, Yiddish professor, psychoanalyst, and biographer of Isaac Bashevis Singer and Allen Ginsberg, died in California on June 23, 2015 at the age of 69. Professor Hadda, who studied and worked at YIVO in the 1960s-70s, was one of the first tenured professors of Yiddish in the United States. Her work is best known for bringing the techniques and insights of psychoanalysis to the study of Yiddish literature.

Read her obituary and a more personal tribute by David Roskies in the Forward.

Two of her colleagues have sent us their reminiscences, and, with their permission, we post them here. Anita Norich, Tikva Frymer-Kensky Collegiate Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature and Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan writes

Janet was one of the most intellectually and emotionally generous people I’ve ever met. In the last weeks of her life, friends and colleagues wrote to her with stories about when they had first met, or a memorable talk she gave, or a conversation that made a deep impression on them, and with heartfelt expressions of love and sorrow. Janet was too alive—too lively—to die, we all felt. Everyone who knew her carries a vivid image of her: short, slim, curly-haired, wearing heels that gave her a couple of inches but could add nothing to the stature we knew her to possess. We also carry vivid memories of her Yiddish scholarship. I met her more than thirty years ago at the first Yiddish conference I attended where she gave a talk about suicide in Yiddish literature (the work that became her book Passionate Women, Passive Men). I remember thinking two things: “You can do that with Yiddish literature?” and “Now, there’s a passionate woman!” It was a passion that made her a wonderful friend and family member, scholar, teacher, psychoanalyst.

We didn’t see one another as often as I would have liked, but it was one of those friendships that always seemed to resume a conversation that we’d left off just the other day. Even on what she knew was her deathbed, she spoke to her friends, invited her patients to come see her (“they will need some closure,” she said), and stayed in the world as long as possible. The last email I sent her was the only one that went unanswered. Her scholarship and her mind were filled with the works of Jacob Glatstein, Abraham Sutzkever, I.B. Singer and more, but I sent her “The Secret” by Denise Levertov because I hoped it might say what I could not find the words to express. It begins: “Two girls discover/the secret of life/in a sudden line of poetry. I, who don’t know the/secret, wrote/the line.” Like the speaker of the poem, Janet would never have presumed to know the secret of life, but the lines she wrote and the conversations she had bring those who mourn her as close to that secret as we can get.

!כּבֿוד איר אָנדענק

Honor to her memory!

Zachary Baker, Assistant University Librarian for Collection Development and the Reinhard Family Curator of Judaica and Hebraica Collections at Stanford University Libraries writes

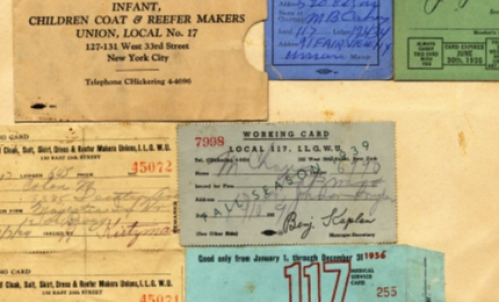

Janet Hadda and I first crossed paths in the summer of 1971, in the Uriel Weinreich Summer Yiddish Program. At the time I assumed that she was a classmate in the Intermediate Yiddish course (the top level offered that summer), but she set me straight a decade or so ago: "I was the TA for that class," which was taught by the then forty-something Mordkhe Schaechter (shprakh - language) and the then twenty-three-year-old David Roskies (literature - literature). Periodically, I would see—and chat with—her in the YIVO Library and at conferences in subsequent years, and after I moved to California in 1999 she visited Stanford on at least one occasion. Janet had a unique perspective on Yiddish literature, informed by her German-Jewish family background and by her psychoanalytic training. She was not an optimist about the future of Yiddish and was quite skeptical concerning the revival of the language and its literature, whether on the part of the youthful cohort that has gravitated to YIVO and groups like Yugntruf, or among the Hasidim. But any disagreements that we might have had on that subject were always couched politely and (on her part, at least) graciously, if firmly. I am grateful to have known her, and I am not alone in that respect.