On Monday, December 9, 2013, YIVO and the Center for Jewish History will host French and Jewish: Defining a Modern Jewish Identity in the 19th Century, in conjunction with anexhibition, a conference and two other public programs celebrating the pinkas (register) of the bet din (rabbinic court) of the Jewish community of Metz, France, two leather-bound volumes preserved in the YIVO Archives. Brimming with details of commercial transactions involving Jews and non-Jews, family law, inheritance, modes of jurisprudence, and recourse to civil courts, the pinkas is a monument to an extraordinary community and its remarkable rabbinical court.

Visit the exhibition web site.

Professor Jay Berkovitz of the University of Massachusetts is the author of the upcoming book, Protocols of Justice: The Pinkas of the Metz Rabbinic Court 1771-1789 (Brill), a transcription and annotated translation of the 400,000 page document.

Here, he is interviewed by Yedies Editor Roberta Newman. This interview is the final in a three-part series.

Professor Jay Berkovitz

Professor Jay BerkovitzRN: Who was the Jewish community of Metz?

JB: The Metz Jewish community pretty much had its origins in the middle of the sixteenth century, when France reconquered Metz and progressively conquered the remaining sections of Alsace Lorraine. The number of Jews in Metz was small but it was a garrison town, and as a result, the Jews played an important role as purveyors of army supplies. Because of that important role, the monarchy was rather supportive of the idea that the community could grow and should grow. From a handful of Jews in the 1550s, there were almost 3,000 Jews by the time of the French Revolution. It was the largest single Jewish community in France prior to the revolution.

It’s an urban setting. Metz is the tenth largest city in France at the end of the eighteenth century and Jews represent seven percent of the population, which is, of course, not insignificant. They had an important role to play in the economy and there are not only those who are native to the community going back to the sixteenth century, but there were more than a few who came from the east. There was a rabbi in the seventeenth century, a Rabbi Narol Cohen, who was a refugee from theKhmel’nyts’kyi massacres. He manages to escape from Poland around 1650, makes his way west to Metz, and is invited to become the Chief Rabbi of Metz, the av bet din, the head of the rabbinical court. In his own person, he really represents the connection between east and west, between Poland and France.

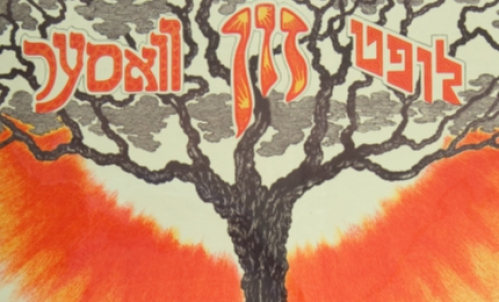

The Metz Jewish community, having become increasingly French in much of its behavior, nevertheless maintained a connection to the east, not just through its rabbi, but also through a prayer that memorialized the victims of the Khmel’nyts’kyi massacres of 1648-1649 and which continued to be recited in synagogues for several hundred years.

So, in terms of the map of European Jewry, Metz must be understood as being as the westernmost post of Yiddish-speaking European Jewry, as very much the western border of what begins in the east with Polish Jewry. It’s all a single cultural unit with variations that are the results of local forces.

The community itself is fairly well-structured in terms of socio-economic sources. There are three classes: an upper, a middle, and a lower class. The upper class of Jews tends to be quite wealthy, of extraordinary means. They have very large contracts with the monarchy for supplying the army and the government, and there is also an evolving international trade. The middle class, of course, is probably the largest, but there is also a significant lower class, that is experiencing life with great difficulty. And the community itself is hard-pressed to supply the kind of support that is necessary: charity, especially; and other means of support that enable people to live. Clearly, the locus of power is the upper class but the community nevertheless operated democratically. Its leadership was typically elected by representatives of the three classes, thirty-three members from each class. So there was an electoral college of ninety-nine that elected the communal leadership and this ensured that the leadership reflected the broader interests of the community. Now, no question that the elites were the ones who would be elected. They had the resources and the time and the education. But at the same time, they knew that they had been selected by a broader section of the community than just their own class.

RN: This pinkas is a snapshot of the community that comes as a pivotal time. It ends two weeks before the storming of the Bastille. Is there anything in the document that portends great changes?

JB: I think that historians will want to grapple with whether there are any trends in the bet din that indicate such an awareness, but I can’t find anything explicit. In fact, I’ll take a step further. Together with the pinkas, there are about a dozen additional cases that are not included in the bound volumes, but they are individual cases. They go from August 1789 to January 1790 and these cases appear to be identical to the kinds of cases that were in the pinkas prior to July 1, 1789, and for the most part, from what I’ve been able to gather, it seems that the bet din continued to operate business as usual. The only thing I see is that there are some occasional references to “difficult times” and references particularly to the difficult economic situation that resulted from the French Revolution. I have not seen any explicit reference to some of the anti-Jewish riots that took place in the late summer and fall of 1789 in Alsace.

Sometimes the pinkas displays a surprising distance from the world around it – not the world of culture, but the political events of the day. There was a fair amount of political activity that would lead ultimately to the French Revolution, not just in1789 but throughout the 1780s. There is no clear evidence of that in the pinkas because it is its own separate universe that occasionally interfaces with the outside world, but for the most part, operates according to its own basic principles.

RN: Did the revolution spell the end of the rabbinical court?

JB: It seems not to have because we have continuing judicial activity at least until January 1790. Now, after that we don’t know, because the records stop. And I can’t say with certainty that because we don’t have any records that means that the court no longer continued to hold its sessions. However, we do know that the grand mark of emancipation was that citizenship was gradually offered and that jurisdiction of cases was surrendered. I assume that that is eventually what happened. It would no longer be possible for Jewish communities to conduct litigation the way it had before. On a private basis, yes; on an ad hoc basis, certainly. Two Jews who have a difference around a monetary matter could certainly come to an ad hoc bet din and have the rabbis resolve their differences. But as a communal institution, it’s very unlikely that in an era of emancipation it would be possible to sustain that kind of institutional activity.

I think that the pinkas is great not only because of what it contains but because of what is symbolizes. It symbolizes the last breath of Jewish autonomy prior to the French Revolution and the story that really deserves to be emphasized here is that this life of autonomy was certainly not primitive, was not anything less than what we would imagine life was after emancipation. Of course, what was missing was the kind of equal opportunity that would become available to all Jews, at least in theory, after the French Revolution. But prior to the French Revolution, there was a rich, vibrant Jewish life that was integrated with French life. And at the same time I think the pinkas speaks to the tension that exists in the present day between maintaining a separate Jewish identity and remaining part of the larger world and society at large.

Interview edited for length and clarity.