Di gantse velt af a firmeblank: The World of Jewish Letterheads

Assemble the letterheads of Jewish organizations, institutions, and individuals in Europe, North and South America, and Palestine from the 1890s to the eve of World War II in 1939 and you have a portrait of the Jewish world: transnational; diverse in language, political, and religious orientation; and flourishing.

Di gantse velt af a firmeblank (The Whole World on a Letterhead) is an experiment in building that portrait. Here, we hope to bring you several times a month, a different example of letterhead from a single collection in the YIVO Archives, the Papers of Kalman Marmor.

Marmor, a Yiddish writer and cultural activist, was born October 11, 1879 in Mayshigola, Vilna Gubernia (today Maišiagala, Lithuania). In 1906, he settled in the U.S. Initially active with the Labor Zionist movement, he later became a Communist. He was an organizer of the 1937 World Yiddish Culture Congress, cultural director of the International Workers Order, and a contributor to the Communist Yiddish newspaper, Morgn Frayhayt. Between 1933 and 1936, he lived in Kiev, where he worked at the Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture and prepared scholarly editions of the work of American Yiddish poets and writers. During Stalin’s Great Terror, the Institute was liquidated, and much of its leadership was arrested and executed. Marmor, an American citizen, returned to the U.S. He died in Los Angeles in 1956.

His papers at YIVO contain several thousand letters from the turn of the 20th century to the 1950s. He had an astonishingly diverse array of correspondents, not limited to Zionist and Communist activists.

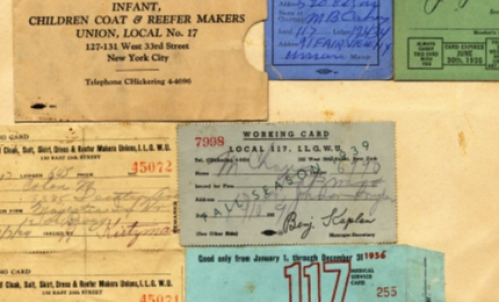

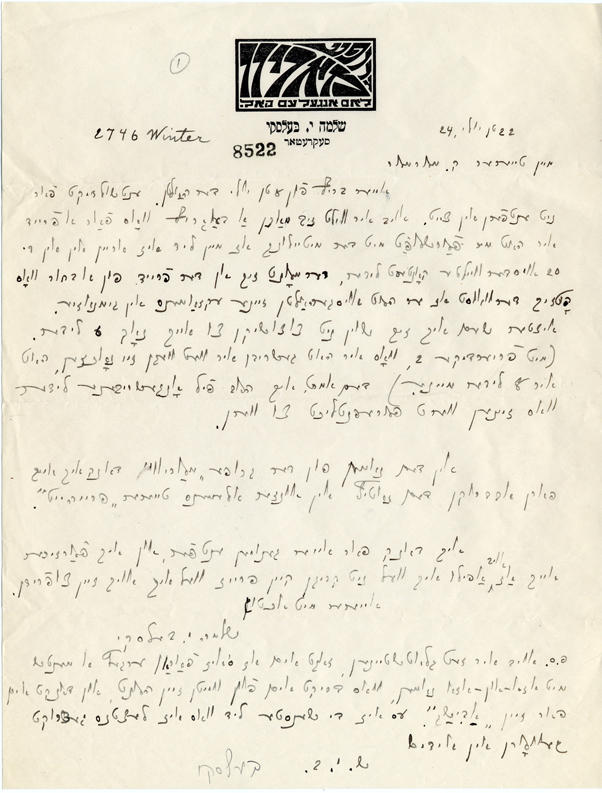

Letter from Shloyme Belski, Secretary of Mariv, Los Angeles to Kalman Marmor, July 24, 1922. (RG 205 Folder 105)

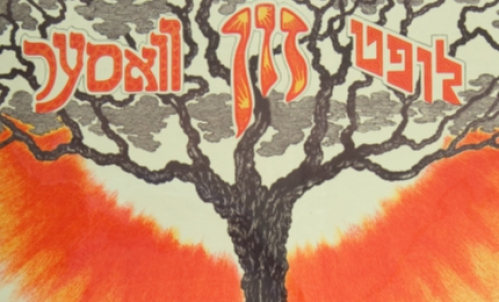

Shloyme Belski (1890-1972) was a Yiddish poet from Belorussia who immigrated to America in 1904 at the age of 14, where he first lived in New York. The year before he wrote this letter to Kalman Marmor, he relocated to Los Angeles, where he became active in leftist circles, including the Yiddish literary group Mariv (West). The Soviet-style spelling of the word mayrev, as it is also commonly pronounced (and which is more traditionally spelled in a way consistent with its Hebrew origin, with an alef and two vovs instead of an ayin and a beys) signals the political orientation of this group right away. Belski also published poetry in the Frayhayt, the newspaper edited by Marmor.

Here, Belski thanks Marmor for the news that one of his poems has been entered into a poetry contest sponsored by the Frayhayt. “You can’t imagine how happy you made me with this news. It’s like the joy of a boy in gymnasium [high school] who learns he’s passed his exams.” In a postscript, he asks Marmor, if he happens to run into the poet Jacob Glatstein, to please thank him for writing the poem, “Abishag,” which Belski considers the finest Yiddish poem of recent times.

Series curated by Roberta Newman; Images digitized by Vital Zajka.