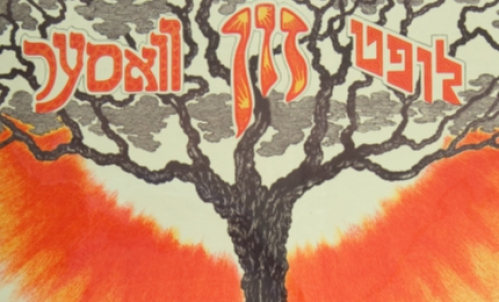

Burning Off the Page: Faith Jones on Celia Dropkin

by LEAH FALK

For the past fourteen years, Faith Jones, Jennifer Kronovet, and Samuel Solomon have returned to the poems of Celia Dropkin, and at long last, their page-facing volume of Dropkin’s selected poems, The Acrobat, has been released from Tebot Bach press with an introduction by poet Edward Hirsch.

Jones, Kronovet, and Solomon began their journey with Dropkin at the Uriel Weinreich Summer Program in Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture in 2000. Last week, I spoke with Faith about the difficulties of translating Dropkin’s unique Belarusian Yiddish, the advantages of publishing with a poetry press, and the pleasures and challenges of a three-way co-translation.

Faith Jones and Samuel Solomon will read from and discuss The Acrobat on July 16th at 6:30 pm at the Museum at Eldridge Street. Attend the event.

Buy the book. Find out more about the feature length documentary about Celia Dropkin, Burning Off the Page.

LEAH FALK: In the epilogue to the book you and your co-translators talk about the project of translating these poems, and note that it took many years. You began at the YIVO summer program, and then you left them and let them sit and then came back to them. What made the three of you return to the poems after that waiting period?

FAITH JONES: You know, I’m not really sure. I guess we all felt like it was sort of unfinished. Some projects peter out naturally, but I think we felt that Dropkin [had to be finished]. Also, there were some changes happening in publishing and especially scholarly publishing, and that was not the place for it to live. It wasn’t that we felt there was some reason internal to the poems or to the project that it wasn’t going forward, but just that we did it at a moment when there were hardly any editions of individual writers’ work being put out in scholarly volumes. And we’d really envisioned the project as a scholarly project. But both Jenny and Sam are poets and Sam is also a literary critic, a professor of literature, and I think we then started to think of the project as more of a poetry project. And indeed, that is how it’s being published, as a poetry book in the format one connects with poetry, and put out by people who know that format well. And with a tremendous introduction by Edward Hirsch, who read the poems and just immediately got them. We were so validated by that.

LF: I loved that introduction. And the book has been getting really wonderful press in the poetry world. It’s really nice to see that for any literature in translation, but especially Yiddish literature.

FJ: It’s quite surprising the way in which the poetry community has embraced this project. Virginia Quarterly, and a number of poetry blogs, and the Poetry Foundation—all kinds of people have given great write-ups. Because we had worked for such a long time by ourselves, away from the Yiddish world and from the poetry world, and we’d sort of been off on our own, it’s nice to see that the poems really do mean something to people.

LF: Translating poetry is notoriously difficult in any language, and it’s not that uncommon for it to be done in teams. You sometimes see books of poems translated by a native speaker and a poet, or a scholar and a native speaker, or some combination like that. The three of you are all translators who learned Yiddish as young adults.

FJ: I wasn’t even that young. But yes, we’re all second language learners, and yes, there were some additional challenges because we didn’t have a native speaker. But we have actually found errors in previous translations of Dropkin, even ones done by native speakers. It’s not always the one-to-one correlation you would expect. Especially when a process takes a long time—you’re going to work out the kinks.

LF: That question wasn’t meant to call you out for not being native speakers, but rather to ask about that three-way collaboration: what were your different roles, how did you each contribute?

FJ: Jenny is primarily a poet, and she also teaches writing poetry and teaches translation. Now her main second language is Chinese, and she’s living in China at the moment, but she hadn’t even started learning Chinese when were learning Yiddish together; she’s learned numerous languages. So she was really the poet among us. And I’m the one who understands tricky and strange things about Yiddish grammar. I’m also a librarian, which means I had the research end, and I had done previous translations, trying to figure out the trajectory of certain poems. And Sam’s story is maybe the most interesting. Sam was in high school when we started this project. And as I mentioned he is currently a professor of comparative literature, so things have changed the most for Sam. Although he was very young, he was always an equal partner in the project, and he really got the literary criticism aspect of it. We had three quite different takes on it. When I translate alone, I primarily translate prose. I’ll do a poem here or there, especially if a poem really grabs me, if I really feel a connection to it, but I don’t think I would do a project this big by myself. So the three of us all had these slightly different angles on it, and I think that really helped us.

We were in our second year when we started this project, so our Yiddish wasn’t that good, and we really learned as we translated. The learning and the translating went hand in hand. We continued to study but we also had to learn from the poetry. So we were all kind of in a similar place in terms of the language, and in a way that was very liberating, because we were all working through the same kind of issues together. I don’t know why this process worked for us in particular. There were certainly many people we had to consult with about many things, such as vocabulary—Dropkin’s vocabulary is not that complex, but she does come from a very specific location, from Belarus, and there were words that we just didn’t know. This was before the new dictionary had come out, there wasn’t a comprehensive dictionary, so we did the best we could. We did often look at the French translation [Dans le vent chaud]. It’s really liberating to look at a translation into another language, because if you look at translations into English, you can go oh my God, I read this poem in a totally different way; am I right, are they wrong? [The French translation] doesn’t have all the same poems, but whenever we needed a word or something, it was really useful. I have Canadian French, enough that I can figure out what’s going on, so we were able to make use of that. It’s a lovely book, done about 20 years ago, so English is definitely kind of behind in terms of getting Dropkin out in translation.

LF: Well, she’s so ahead of her time thematically; that doesn’t surprise me much.

FJ: I think she scared a lot of people.

LF: I’m struck by the motifs that show up in this particular selection of poems: the motif of knives for example, or ways in which the body is altered or used or fed upon—did you run into challenges in tracking those motifs across the poems, wanting to keep them consistent or respect her unique use of certain patterns?

FJ: We didn’t really look at all the poems together and decide to always translate a word in a particular way, or try to keep certain images recurring. How we chose the poems in this collection was that we translated all her poems, then chose the ones that we thought we could make into good poems in English. And if we thought that we were able to work with the poems so it would be a good English-language poem, then that’s what ended up in this book. The poems, even some of her quite important poems, that we did not think we knew how to work with, or that lost something in the translation that we didn’t think would be regained, we didn’t keep. We have drafts somewhere, and from time to time people will email me and say I’m using this poem with my class, do you have this poem in translation, and I’ll email them our draft. But they’re not poems that are great English poems, so those are still available to the next translator out there. We weren’t able to capture them in the way that we felt really did them justice.

In terms of the motifs—one of the things that’s so striking about Dropkin is how few of the motifs are particularly Jewish, and how often she borrows motifs from other things. Occasionally there are things that come from Jewish history or the Bible or something, but more frequently, classical images or Christian images.

LF: Ed Hirsch notes the way she even puts herself in a Christ-like position in the poem “Suck.”

FJ: She doesn’t seem at all worried about that. So she really is a modernist: anything can be used by anybody. There doesn’t have to be Jewish content, there doesn’t have to be a Jewish message, it doesn’t have to enrich the Jewish people—she just uses whatever it is that she thinks is the most interesting symbol, or the one that captures what she’s looking at. So we tried not to mask that. We didn’t want to turn her into someone’s Eastern European bubbe. She was a very modern bohemian person who was very interested in individual liberation. So I just wanted to make sure all those things stayed in the poems. That made us unafraid to use words that worked in general, that weren’t necessarily from a Jewish context. In one draft of one poem we actually used the word “baptized,” and we had long fights with everybody about that. In the end we ended up not using it, and it wasn’t the word she used in the original, but that’s the kind of thing that we felt quite clear to call on other traditions for if it was going to get the right image across. And that was very liberating. Her stuff about the body—it’s fascinating. It’s scary at times—so many things about the body being eaten from the inside. She had rheumatic fever in her thirties, after which she was unable to dance. Her son talked about how much his mother’s joy in life changed when she couldn’t’ dance anymore. Plus she was extremely ambivalent about childbirth and being a mother. You can see she loved her children; notwithstanding, she had quite a lot of ambivalence about it. I think there’s a basis there, both physical and metaphysical, for those images. And I find them stunning. They’re one of the main reasons I keep reading Dropkin.

LF: That’s another thing that makes them feel very contemporary: acknowledging that motherhood is both a pleasure and a pain. How do the themes of Dropkin’s work fit into the poetry of other female Yiddish writers in New York at the time?

FJ: She had friends in a number of different literary movements. But she felt the best poet writing in Yiddish was Anna Margolin. They were friends, and her son remembered being taken to cafes when his mother would go and meet other poets, and one of them was Anna Margolin. They weren’t close friends, but they seemed to admire each other poetically, and would have intense discussions about poetry together. I think a lot of women writing in Yiddish back then wrote really outside a formal movement; that seemed to be the norm. So in that way Dropkin wasn’t anomalous, she was more like the other women than like the men.

But none of the other women wrote as explicitly as she did. And of course, really, she didn’t—everything is metaphorical—but she was the most sexually and bodily explicit of pretty much any writer in Yiddish. But all of the women tended to be more embodied than men; you find discussions and descriptions of the body. So I don’t think she’s a complete anomaly. She’s unusual, and she’s the one who took it the furthest.

LF: Was it your choice as translators or the publisher’s choice to present it as a page-facing translation?

FJ: We wanted it—but we were scared that a publisher was going to say no. We felt that facing pages was just so much better for the reader and the work and we were so thrilled that the publisher agreed. It’s twice the pages, but we brought it down to a pretty lean collection. So the collection is not the hugest collection of her work; but it keeps it down to the length of a poetry book, about 100, 120 pages.

LF: What’s your ideal audience if this translation reaches a combination of both Yiddish speakers and new, monolingual English readers?

FJ: The nice thing about having a poetry press as a publisher is they know how to reach people who love poetry. So my hope is that people who haven’t been aware of Yiddish poetry in the past, people who love modernist poetry and are interested in how it advanced in different language traditions, would be a normal kind of new audience for Dropkin. In the past, we’ve seen her work almost entirely in books of Jewish poetry or in Yiddish poetry in translation—for people who already know they’re interested in Jewish or Yiddish poetry—so I hope this poetry press will help that reach. Of course, I want all the people who’ve been loving Dropkin all along and have been rooting for us to read it, and I hope we can bridge that gap in Yiddish studies classes and modern Jewish literature courses, and in modern poetry courses, so that people who love poetry, people who love Yiddish, all those people will be reading the poems.

Leah Falk is YIVO’s Programs Coordinator.