Adelebsen: The Records of a Jewish Community in Germany (YIVO Archives, Record Group 244)

by VIOLET LUTZ

Of the many interesting materials that I've encountered in the YIVO archival collections that I have had the honor and pleasure of processing as an archivist at the Center for Jewish History, I am struck sometimes by particular items that offer insights into everyday life in a particular time and place. The Adelebsen Jewish community records held by YIVO, dating from 1830 to 1917, contain remarkable traces of the evolving Jewish communal life in the small German town of Adelebsen, in the district of Göttingen, in what is today the state of Lower Saxony. The region was historically part of the kingdom of Hanover. (The latter was annexed by the kingdom of Prussia in 1866; and subsequently became part of the German Empire, founded under Prussia's leadership in 1871.)

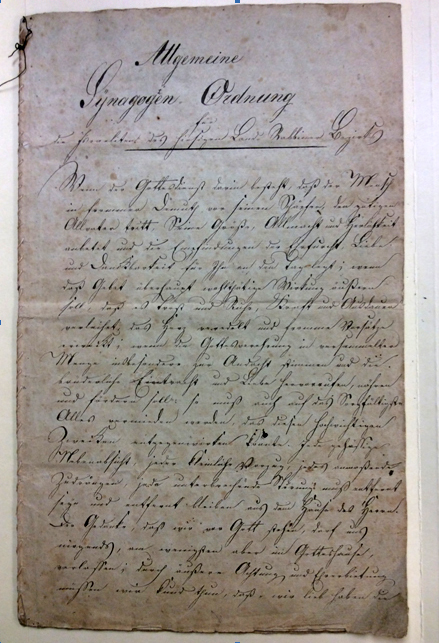

Among the items in the collection that reflect noteworthy changes in communal life is an original handwritten copy of the synagogue regulations for Hanover (Synagogenordnung), dating from the time they were instituted, in 1832. The regulations were issued by Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler, who is otherwise well known as chief rabbi of Great Britain (1845-1890). In 1832, Adler held the office of Landrabbiner in Hanover, a government-appointed position overseeing all the Jewish communities in the region.

Synagogue regulations of 1832.

Synagogue regulations of 1832.(TRG 244 also contains minutes of meetings the Adelebsen Jewish community held with Rabbi Adler in 1836 and 1844, on occasions of his visits to the town.)

In earlier times it was not unusual to have loud talking and a certain amount of commotion going on during synagogue services, including the auctioning of synagogue honors. However, in the early 19th century, Jewish communities in towns and regions throughout the German states adopted regulations like those of Adelebsen, that, among other things, provided rules for behavior during synagogue services, in order to ensure a quieter, more orderly, and what was perceived to be a more dignified atmosphere. According to scholar Michael A. Meyer, this new stress on decorum, which was neither contrary to Jewish law, nor specifically Christian in nature, represented a cultural shift in the religious life of German Jews, as compared to Ashkenazi tradition. It was reflective, in part, of their growing participation in the wider German society.

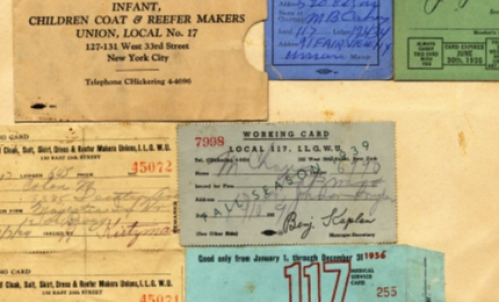

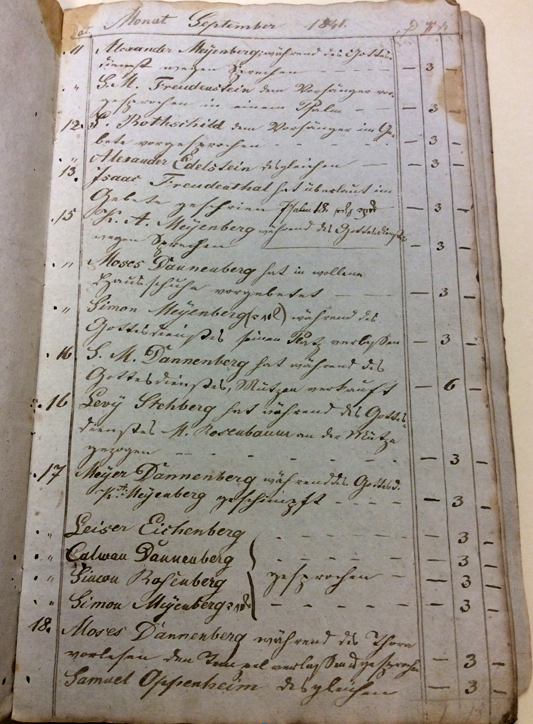

The leaders of the Jewish community enforced the synagogue regulations by fining members who violated them. The Adelebsen records from the 1840s include two account books recording fines collected, with the specific reasons given, such as talking during services, creating a disturbance, being inappropriately dressed (e.g., not wearing a hat), leaving before the end of services, or bringing an infant along.

Synagogue fines account book, 1841

Synagogue fines account book, 1841The community's copy of the Hanover regulations also contains appended revisions made in Adelebsen, dated 1841 and 1845. In 1841, it is noted, for example, that older people are allowed to leave the service if they need to, without penalty; that the fathers of misbehaving children over five years old are responsible for appropriately punishing them; and that snuff tobacco and pipes are not allowed in the synagogue. One of the clauses added in 1845 states that all of the foregoing rules apply just as well to women as to men.

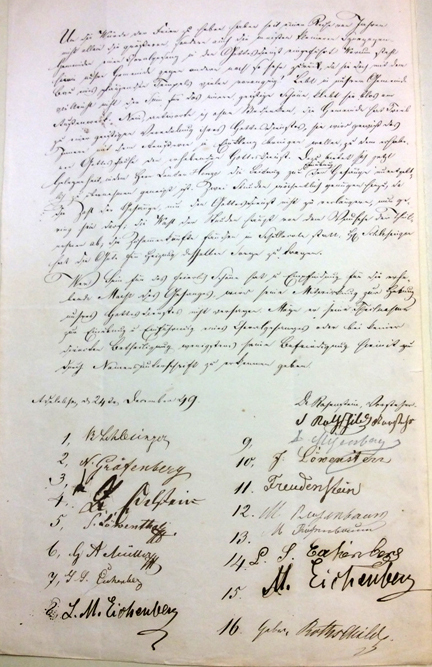

Another striking document in the records of the Adelebsen community relates to the adoption of choral singing during synagogue services: it is a circular letter from 1849, in the hand of Dr. Heinemann Rosenstein, superintendent (Vorsteher) at the time, arguing for the founding of a synagogue choir, and calling for members to add their signatures to show their willingness to participate, or even just their support of the idea.

Circular letter about forming a choir, 1849

Circular letter about forming a choir, 1849The letter is co-signed by J. Rothschild, the account keeper, and, in numbered entries, 20 other community members signed on, presumably voting members, representing heads of households. At this time Adelebsen had all together approximately 192 Jewish residents, who made up about 13% of the town's total population.

Some German-Jewish reformers at this time saw the institution of organized choral singing as one way of elevating the atmosphere of religious services and reinvigorating religious practice, especially for the younger generation. This attitude is reflected, for instance, in the mission of the contemporary German-Jewish periodical Liturgische Zeitschrift zur Veredelung des Synagogengesangs mit Berücksichtigung des ganzen Synagogenwesens (Liturgical journal for the edification of music in the synagogue, with consideration of the entire synagogue life), which, in one of its first issues in 1848, reprints an essay from cantor and teacher J. Wimmelbacher (first published in 1838), "Der Gesang als wesentlicher Theil des Gottesdienste” (Song as an essential part of the religious service) (s). Wimmelbacher, who worked with cantor Maier Kohn in Munich, offers the synagogue choir there as a shining example for others, arguing that "song with a rehearsed choir fills a need in our era, marked by the striving to fill the house of worship with sacred dignity, pious devotion, and solemn stillness."

Along the same lines, Dr. Rosenstein notes in his circular letter that choral singing had been introduced in many other Jewish communities, both large and small, in order to "heighten the dignity" of the service. Referring to the Adelebsen community's new synagogue — built in the late 1830s upon the urging of Rabbi Adler — he reasons:

Is our community concerned only with the visible aspect of religious life? — no, I say, without hesitation: the community has the desire for the spiritual elevation of the religious service too, and will certainly now want to bring the inner and the outer aspects into harmony, by joining the inspiring house of worship with a similarly inspiring service.

Dr. Rosenstein indicates that the cantor is willing to donate his time for a two-hour weekly rehearsal, which would be adequate, he says, since the number of songs would be few — in order not to detract from the service itself.

(Originally from the nearby village of Lüthorst, Dr. Rosenstein, who received his medical degree at the University of Göttingen in 1840, headed the Adelebsen community from 1848 to 1850. After that he settled in Einbeck, where he gained local renown as a “doctor of the poor,“ due to his generosity in treating indigent patients free of charge, and as an advocate in educational and cultural matters. On his 50th anniversary as a physician, in 1890, he was fêted by Einbeck citizens, and awarded the imperial Order of the Red Eagle, 4th class, for his civic service.)

The records contain no further evidence about whether or not the Adelebsen community established a choir in 1849 — perhaps it never actually got underway. But a choir seems to have been established in 1862 under the leadership of the Jewish teacher and cantor Sally Blumenfeld. In a letter Blumenfeld writes to the community executive body (Vorstand) in April 1862, he refers to a recent circular letter in which the community "unanimously" expressed its wish for a "four-part mixed choir," and he urges the leaders to call a community meeting about it.

Another letter from Blumenfeld several weeks later is accompanied by a draft resolution outlining rules for the choir. Those who wanted to participate were called upon to commit themselves to attending regular rehearsals, and to showing up on time to take their assigned places at services. One clause notes that women would probably have difficulty meeting the specified obligations (presumably due to their domestic duties) but are expected, at a minimum, to appear regularly at rehearsal if they want to participate. The resolution also appoints a five-person commission to attend to the practical arrangements and oversee choir members' adherence to the rules.

Blumenfeld was a prominent personality in the life of the community, being the sole teacher at the Jewish school for nearly 50 years, from 1861 to 1910. The more than a dozen surviving letters by him are another highlight of the collection.

See a finding aid (guide) to this collection.

References

Meyer, Michael A. "Jewish communities in transition," chapter 3, in: Meyer (ed.). German-Jewish History in Modern Times: Emancipation and acculturation, 1780-1871. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Wimmelbacher, J. "Der Gesang als wesentlicher Theil des Gottesdienstes," Liturgische Zeitschrift, vol. 1, no. 3, p. 31-34. http://archive.org/stream/liturgischezeits11unse#page/n23/mode/1up