“A Place Where Polish-Jewish Relations Could Start Anew”: Interview with Kamil Kijek

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

Almost immediately after the end of World War II, a new center of Jewish life in Poland began to take shape in western Poland, in Lower Silesia, a formerly German territory de facto awarded to Poland in the Potsdam Conference of July 1945.

Kamil Kijek

Kamil KijekThis little-known chapter of postwar Jewish life is the topic of research now being conducted by Dr. Kamil Kijek, a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Jewish History. His study, entitled “Polish Shtetl after the Holocaust? Jews in Dzierżoniów, 1945–1968” focuses on one particular town in Lower Silesia, which was settled by survivors who stayed in the region after liberation. They were later joined by Jews repatriated from the Soviet Union, and others who had survived in hiding in Poland or returned from concentration camps in Germany. Jews also migrated to the region to escape anti-Jewish violence in central Poland, including the 1946 Kielce pogrom. There were soon enough Jews in Lower Silesia to make it a good base for revival of Jewish life in Poland.

There were a number of factors that enabled the region to assume such importance in the early postwar years. The idea of lopping off parts of eastern Germany and transferring territories to Poland had been hatched well before the end of the war by Stalin and Polish Communists. In 1945, when the war was still raging, and Soviet and Polish troops were already in Silesia, Kijek suggests, "there was a political game being played, because you need to create facts on the ground to show that the Poles were already there, that there was a strong Polish presence there.”

The “strong Polish presence” was made up, to a large degree, of Jews. There was a large concentration camp in Lower Silesia, Gross-Rosen, with important branches in Dzierżoniów and in two additional nearby towns. There were about 20,000 Jewish survivors of the camp and, Kijek notes, "Accidentally, part of that group was made up of Polish Jews, the only prewar citizens of Poland who were there on the spot.” They were not very eager to go back to their hometowns from before the war because of the decimation of their communities and the fear of antisemitic violence. (This was in contrast to displaced non-Jewish Poles, who, for the most part, did go back to their original places of residence after the war.)

Lower Silesia’s German population was gradually deported and the Polish authorities considered the territory to be “empty.” The government sent Jewish repatriates (as well as non-Jewish Poles) there to resettle it. And so, early on, the territory had a reputation of being a center for Jewish survivors, where people might reunite with relatives and friends from before the war. "After the Holocaust, the need for building any connection, even if you'd lost your entire family and this was only a friend from the shtetl, was all-important,” Kijek reports. “These ties strengthened the community."

He conducted interviews with residents and former residents of Dzierżoniów in Poland, Israel, and the United States. "They told me that whenever a transport train arrived, people came to the train station to see if maybe someone they knew was among the new arrivals."

Children in a Jewish orphanage gathered for a celebration in honor of the Red Army, Pietrolesie, Lower Silesia, 1946. Portraits of Lenin and Stalin adorn the altar and the Polish banner reads, “Long Live the Red Army! Long Live Polish–Soviet Friendship!” (YIVO)

Children in a Jewish orphanage gathered for a celebration in honor of the Red Army, Pietrolesie, Lower Silesia, 1946. Portraits of Lenin and Stalin adorn the altar and the Polish banner reads, “Long Live the Red Army! Long Live Polish–Soviet Friendship!” (YIVO)Dzierżoniów (formerly known as Reichenbach) was also important for two key reasons. It was the first headquarters of the local branch of the Jewish Central Committee, which then moved to the nearby city of Wroclaw in 1946. This group and its leaders sought to strategically combine loyalty to the agenda of the Polish state with the goal of achieving partial Jewish national autonomy in Silesia. And, more than half of Dzierżoniów’s 20,000 inhabitants were Jewish. This makes it almost unique in Eastern Europe after the Holocaust. The Jewish population decreased sharply after 1946, when news of the Kielce Pogrom drove thousands of Jews to flee Poland, but even then Jews remained a high percentage of the population (about 20-30 percent) for at least another decade.

"It wasn't a shtetl, wasn't like a Jewish community from before the war, but it was something special—both drawing on the past and yet something entirely new," Kijek points out. This is a key area of interest for him. "How much of the ways of the shtetl, the understanding of the social space by both Poles and Jews, was regained and how much was lost and shaped anew during the era of life under Communism?"

He suggests that Dzierżoniów served as "a laboratory for new Polish-Jewish-German relations." Since almost all of its inhabitants, Jewish and non-Jewish, were from elsewhere, “it was a place where Polish-Jewish relations could start anew. People brought their memories, superstitions, and assumptions about the other group but, on the other hand, they started from anew." It was also a laboratory for Polish-Jewish-German relations. "There were still Germans there,” Kijek notes. “The last of them weren't deported until the 1950s."

Kijek;s interest in Dzierżoniów is personal as well as scholarly. He was born there in 1981 and his parents still live there. He completed his dissertation on “Socialization and Political Consciousness of the Jewish Youth in Interwar Poland” at the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Science in Warsaw. Currently, as a member of a research project based at the University of Warsaw, he is working on the topic “Anti-Semitic violence in Poland in 1930s and Jewish reactions towards it.” In October 2015 he will begin teaching in the Jewish Studies Department at the University of Wroclaw, Poland.

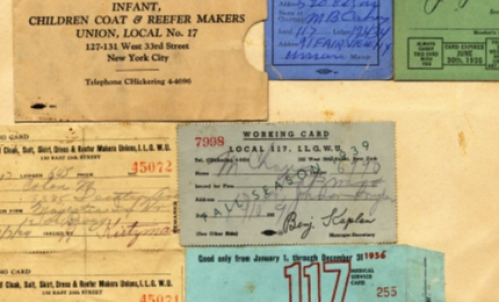

During his one-year fellowship at the Center of Jewish History, Dr. Kijek will research various collections of its partner organizations, including several key collections at YIVO. "I'm overwhelmed by the amount of material that YIVO has," he says, citing, in particular, RG116.3, Territorial Collection, Poland, materials on Jews in Poland after World War II which pertain to efforts to reconstruct Jewish life in that country; and RG 541, Papers of Jacob Pat.

Pat, a writer and Jewish labor leader, arrived in the United States shortly before the outbreak of World War II, but then went back to visit Poland after the war. He wrote extensively about his impressions of postwar Poland in books and articles. "It wasn't clear whether there was a future for Jews in Poland or not,” Kijek notes, “but Pat was among those who thought, at least in 1946, that some kind of a future was possible."

YIVO also awards yearly fellowships and research grants to scholars. The awardees for 2015-2016 will be announced at the end of February.