“What Would Yiddish Be Without Hebrew?”: A 20th-Century Debate

by MAURICE WOLFTHAL

In 1931-1932, a mere twenty years after the Czernowitz Conference declared Yiddish “a national language of the Jewish people,” Nokhem Shtif and Max Weinreich (both pioneering scholars in Yiddish literature and linguistics and both activists in secular Jewish causes) engaged in a public debate on the language they loved, in a charged political context.

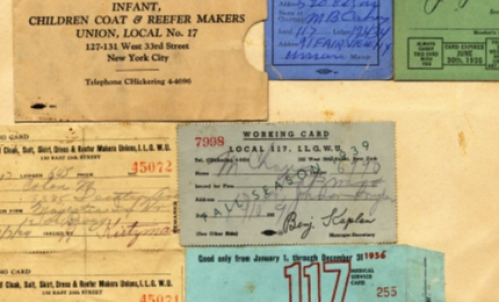

Shtif had circulated a memorandum that led to the creation of the YIVO in 1925 in Vilna, and Weinreich assumed a vital leadership role in YIVO. But Shtif moved to Kiev in 1926, attracted by Soviet funding for Yiddish culture and the promise of a good salary as head of the Department for Jewish Culture at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. One of the aims of YIVO’s founders was the systematization of Yiddish orthography, and great efforts were made towards that end. The Soviet government, through its Jewish institutes, promoted the phonetic spelling of Yiddish words of Hebrew/Aramaic origin, which made reading easier and furthered its ideological aim to disguise those origins, which were denounced as being “nationalistic,” “religious,” and “Zionist.” Nokhem Shtif and his journal, Di yidishe shprakh (Yiddish Language), embraced Soviet Yiddish orthography.

The stage was being set for Stalin’s Great Purge. Tens of thousands of Soviets were falsely accused of treason, espionage, “Trotskyism,” and other supposed offenses. Many were coerced into “confessing” their crimes. Thousands were fired from their jobs, expelled from the Communist Party, deported to slave-labor, or murdered outright. The Jewish victims were primarily rabbis, Zionists, and Bundists. Shtif was soon demoted. His department was replaced by the new Kiev Institute for Jewish Proletarian Culture, with Yoysef Liberberg (a member of the Communist Party) as its head, though Shtif continued to lead its Philological Section. And in 1928 both he and Liberberg were publicly reprimanded for inviting Simon Dubnow (the eminent historian with whom Shtif had worked on behalf of pogrom victims and founder of the Folkspartey) to attend the opening of the Institute.

Meanwhile, Weinreich had immersed himself in the growing network of Yiddish schools of the Tsentraler bildungs komitet (Central Education Committee) in Vilna and taught at its Yiddish Teachers’ Seminary. He served as the research secretary of the YIVO’s Linguistic Section from its inception, spearheaded many of its projects, and directed its aspirantur, the training of graduate students. When the YIVO organized an Orthographic Commission, he took part in the bitter debates concerning the spelling of words of Hebrew/Aramaic origin. Politically, he was a sympathizer of the Bund, the General Jewish Labor Union of Lithuania, Poland, and Russia, which was still the largest secular Jewish organization in Poland.

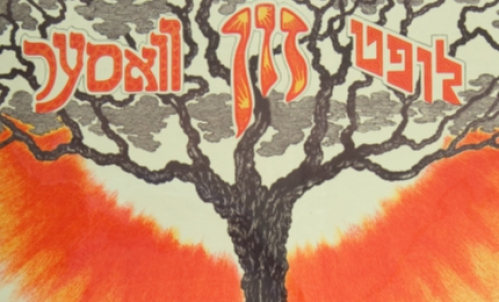

By 1929 Weinreich was on the Board of Directors of the YIVO. And that year in Kiev Shtif went much further in endorsing the Party line than the campaign for Soviet Yiddish orthography when he published “Di sotsiale diferentsiatsye in yidish: di hebreyishe elementn in der shprakh” (Social Differentiation in Yiddish: the Hebrew Elements of the Language) in his official organ, Di yidishe shprakh, in which he derided the Hebrew component of Yiddish as a reactionary relic of the religious and upper classes and called for systematic “dehebraization.”

“Vos volt yidish geven on hebreyish?” (What Would Yiddish Be Without Hebrew?) was Weinreich’s scholarly and spirited rebuttal of 1931 in the New York Yiddish journal Di tsukunft (Future). Shtif responded in 1931 and 1932 with “Revolutsye un reaktsye in der shprakh” (Revolution and Reaction in Language) in his journal, now renamed Afn shprakhfront (On the Language Front).

Shtif died in 1933, at the age of 54. Weinreich wrote a generous three-page obituary in Di tsukunft that heaped praise on Shtif’s massive scholarly contributions and extolled his passionate idealism. Weinreich emphasized Shtif’s lifelong service to the Jewish people, stressing that even as a revolutionary in tsarist Russia, Shtif had insisted that Jews faced special problems that a revolution would not – as others maintained – solve automatically. As for their recent polemical clash, Weinreich made only passing reference to Shtif’s attacks on Hebrew, asking rhetorically whether they had really been the result of Shtif’s “organic development” or of some sudden pressure.

In addition to “Vos volt yidish geven on hebreyish?” Maurice Wolfthal has translated Yitzhak Erlichson’s Mayne fir yor in sovyet-rusland (My Four Years in Soviet Russia) for Academic Studies Press (2013); excerpts from Nokhem Shtif’s Yidn un yidish (The Jews and Yiddish) for Ingeveb, a Journal of Yiddish Studies, Oct. 4, 2015); Bernard Weinstein’s Di yidishe yunyons in amerike (The Jewish Unions in America); Nokhem Shtif’s Pogromen in ukrayne (The Pogroms in Ukraine); and four novellas by Ayzik-Meir Dik. His translation of Shmerke Kazcerginski’s Khurbn vilne (The Destruction of the Jewish Community of Vilna) is forthcoming with Wayne State University Press.