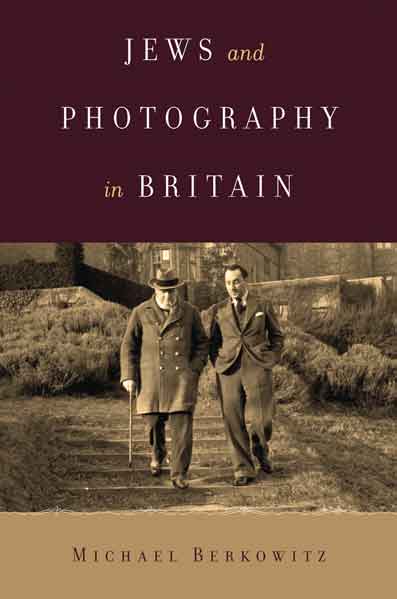

Jews and Photography in Britain: Interview with Michael Berkowitz

Richly illustrated with both color and black-and-white images, Jews and Photography in Britain is the first historical investigation of prominent roles played by Jews in the history of photography in Britain. From the mid-nineteenth century to the 1970s, Jews were prime movers behind nearly all things photographic in Britain, including photojournalism, portrait studios, collecting, applications of photography to the fine arts, and the emergence of photography criticism and history as distinct fields.

For instance, a great many studio and street portrait photographers had Jewish origins. As a "new" profession, photography was more open to Jews than some other branches of journalism and the arts, and British Jews took advantage of this opportunity to earn a living and have an impact on British culture as a whole.

Michael Berkowitz is a professor of modern Jewish history at University College London and editor of Jewish Historical Studies: Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England. His previous books include Zionist Culture and West European Jewry Before the First World War (1993), The Jewish Self-Image: American and British perspectives 1881-1939 (2000), and The Crime of My Very Existence: Nazism and the Myth of Jewish Criminality (2007).

Buy the book.

Professor Berkowitz is interviewed here by Roberta Newman.

RN: Were Jews similarly prominent in the history of photography in other countries? Or was there a particular reason for their prominence in the field in England that is not duplicated elsewhere?

MB: Compared to Britain, it's safe to say that Jews were well out of proportion to their numbers, in photography, almost everywhere in Eastern and Central Europe. One of the reasons why photography was such a Jewish-friendly area in Britain is because photographers, even at high levels, were considered "tradesmen" – not the kind of esteemed vocation that a respectable, non-Jewish Englishman would choose. (I give Francis Hodgson, photography critic for the Financial Times, credit for this insight.) In less urbanized parts of Eastern Europe, I believe that Jews' prominence in photography grew out of the kinds of "middle-man" roles they filled in serving the needs of the landed gentry.

RN: Is there a particular lacuna you were hoping to fill with your book? Indeed, there is no existing book on the subject you wrote about, but beyond that, has there been much written about the role of Jews in British culture as a whole?

MB: In the beginning I was trying to fill a gap. I thought I was writing a different book in which Britain would have a minor role. But the more I found, the more the subject became something substantial and was no longer the filling of a gap – but the heart of the story itself. I attempted to go beyond a discussion of Jews' "contributions" to show how the whole history of photography might look different if ethnic difference is taken into account. In that way I was (with the greatest respect) following the lead of Joan Scott's approach to women's history. She proposed that historians should not only ask "what women did' or 'contributed" but how all of history looks different when women are integrated into the investigation from the outset.

There is a great deal written about Jews in British culture, and much of it is excellent. But a lot of the other work is inclined toward politics and religious life, or tends to focus on individuals. And the national setting aside, it has been challenging to write about Jews in secular culture.

RN: Were Jews as prominent in other fields of British culture as they were in photography?

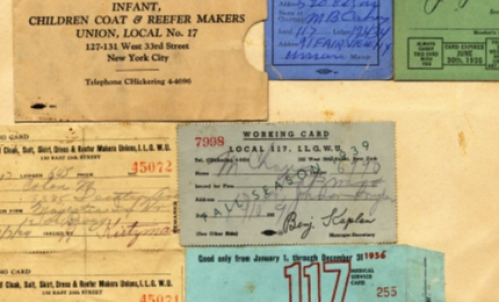

MB: Although not quite at the same level as in the United States, Jews were prominent – but usually not as Jews – mostly in the world of entertainment. And of course Jews were major figures in the garment trade in numerous ways. James Jordan has almost totally overturned previous thought about the absence of Jewish engagement with the BBC. Jews also were overly active in early British film, but not much has appeared on this to date.

RN: Are Jews less visible on the whole in England than they are, say, in the United States?

MB: It is important to remember that the numbers of Jews are much smaller in the UK than the United States. The culture itself is quite different, which stresses a kind of conformity that Jews, overall, embraced. But it also is crucial to see some of the great contradictions. Disraeli, while not technically Jewish, was regarded by many as a "Jewish" Prime Minister. Visibility is a very complicated notion – because often it was a matter of someone's Jewishness not being talked about openly or directly. One of the major figures in my book, James Jarche, never says outright that he is a Jew. It is not just a matter of avoidance – it might be considered either impolite or unnecessary to mention it.

RN: The photographers you write about were secular Jews and you don’t try to make the point that there was anything overtly “Jewish” about their work. So in what lies the significance, for the history of British photography, that so many of its developers and practitioners were Jewish?

MB: I would qualify that for a select number, such as the editors and agency heads like Stefan Lorant and Bert Garai – especially in the area of photojournalism – there was something overtly Jewish about their work, if they had the opportunity to choose their own subject matter. For many Jews their secular Jewishness took the form of anti-fascism.

A great deal of my book concerns the activities of Helmut Gernsheim, who is one of the most important figures, of all time, in the history of photography. There is no question that he was always treated as a "foreigner," which was shorthand for Jew. Gernsheim could not have lived the life he did, in Britain, if he had not come as a refugee from Hitler's Germany.

But more generally speaking, due to their particular historical situation, Jews introduced approaches to photography that helped to make it more popular, accessible, higher-quality, and culturally significant. It is, therefore, a part of Jewish social, cultural, and economic history that is not well known. It is important for me as a historian to see how Jews actually lived, and photography is a part of this that we have tended to take for granted. To put it another way: it's similar to giving an author or an artist credit for a work which had previously been unattributed. Photography changed, not only technologically, but historically and in its social functions, and Jews played an extraordinary role in how this happened--in part due to the field's openness to them, and also because other areas of creative and arts-based vocations were not as accessible.

RN: What draws you to the study of visual culture? You have previously also written about Zionist iconography.

MB: I'm drawn to visual culture in part because of my own origins. I'm from Rochester, New York, the home of Eastman Kodak. My father worked at Kodak Park as a metal fabricator. In the late 1970s I was employed, in the summers, in the film emulsion melting division. So I have a rather unusual appreciation for how film and cameras are made. My father was quite a good amateur photographer.

I also learned, when a cousin in Israel contacted me, that a branch of my family, the Jasvoins, had been active in photography in Eastern Europe. My father is named after his mother's grandfather, Wulf Jasvoin, who was one of the court photographers in St. Petersburg. Other members of the family had studios and eventually established photo equipment stores in Kovno (Kaunas) and elsewhere in Lithuania.

I also must give credit to my mentor, historian George Mosse, who always insisted, in the way he approached cultural history, on the importance of what people see in addition to what they read.

Read Michael Berkowitz's article about Queen Elizabeth II and her relationships with Jewish photographers in The Jewish Chronicle, "Behind the public face, a clear portrait emerges."